In a previous post, I began an excursion into how science presenters can be easily and unwittingly seduced into giving very poor presentations by dint of their training and facilitation of their professional association’s publication standards.

It was left with a complex diagram I often use in my workshops about IT where I try to persuade late adopter colleagues to review their relationships with technology and give thought to how best to bring themselves up to date (hint: buy an iPad).

The diagram was designed in 2008 by Nick Felton at the request of two New York Times op-ed writers, W. Michael Cox and Richard Alm, and his complex graph was then repurposed by Apple pundit, Horace Dediu, in 2012.

The link to the original NYT article is here, and the Dediu link here.

I want you to see in part how I use this diagram, employ Keynote in doing so in my workshops, and give you an idea of how I discuss it via my voiceover. It will begin a discourse on charts and graphs, one of the essential tools for scientists which can either make their presentations clear and engaging, or become utter turnoffs in their obfuscation. The video is 5 minutes long. I’ll wait…

What I wanted you to see is that it is possible to take a complex diagram rich with information, and interact with it to better engage your audience. And to combine another’s analysis of the same data but a different purpose using some of Keynote’s most useful elements – Magic Move – to make a segue between the two.

This leads to:

Unwitting mistake #6: Poor use of data-rich charts and graphs

Let me say at the outset that I have a rule of thumb that I apply to graphical portrayal of data:

Use these rich sources of presentation persuasiveness wisely. They are not things you show because science demands it, but because they serve a purpose. Because of the latter, you owe it to your audience to help them understand what you are trying to convey showing your graphs and charts.

There is a corollary to this rule of thumb, and it relates to a point I made in my previous blog entry about audiences varying between having superficial subject knowledge through to the profound. The corollary is this:

The less your audience knows your subject or is unfamiliar with the use of graphs and charts, the more you need to gently step through your graph, building up each component in a coherent story telling. The addendum to this applies the same narrative to hostile or skeptical audiences.

Let me illustrate with one of the greatest expositions of graphs as story telling in recent public memory. It starts with Steve Jobs introducing the original iPhone at Macworld in January, 2007. One where he embarks on a persuasive story of why the iPhone was created, and why it has a chance of succeeding despite various pundits and competitors saying its market was “mature” (unchangeable) and the iPhone was too expensive.

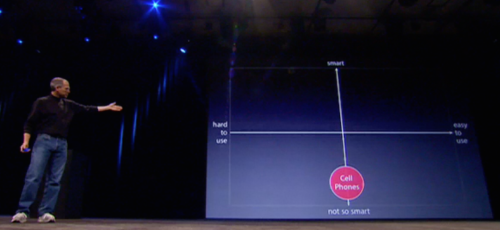

We start here with a screenshot, below, from Jobs’ iPhone keynote. If you have the entire 2007 keynote (available on iTunes or YouTube), it starts about 30 mins in. Jobs has just been discussing the properties of the current (2007) crop of “so-called” Smartphones, and wants us to know the iPhone has a place in the universe. He claims it’s because the current crop are neither that smart nor, in particular, easy to use. In other words, the current mature telco industry is saying, “You can have smart, you can have easy, but you can’t have both. We don’t know (or care) how to do that”.

For Apple, that is an industry worth challenging because the status quo has been accepted as unchangeable (A little like the science presentation scene, no?).

Jobs starts us on his journey of challenge – his narrative of why the iPhone is the right risk for Apple to take – with this simplest of graphs:

Jobs “cubes” this graph in, and then says,

Jobs “cubes” this graph in, and then says,

“If you make a Business School 101 graph of a smart axis (Y) and an easy to use (X) axis….”

That gets an audience laugh perhaps because of Jobs’ use of a really simple graph together with his “I’m-almost-embarrassed-to-say-it” expression of, “Business School 101”. What Jobs is about to do is school the telco industry using the most basic analysis of why they are wrong. Next:

Jobs now slow builds in a circle showing the placement of the current majority of phones in use – dumb or feature phones – near the extreme of the “not so smart” Y Axis. They are zero on the X “ease of use” axis because that’s not why people buy them – it’s a given, and not a branding element. No one is claiming our phones are easier to use than our competitors, because all they do is make calls and send texts. (In fact, I always thought Nokia’s range of dumb phones possessed the most superior User Interface, compared to Ericsson or Motorola).

Jobs now slow builds in a circle showing the placement of the current majority of phones in use – dumb or feature phones – near the extreme of the “not so smart” Y Axis. They are zero on the X “ease of use” axis because that’s not why people buy them – it’s a given, and not a branding element. No one is claiming our phones are easier to use than our competitors, because all they do is make calls and send texts. (In fact, I always thought Nokia’s range of dumb phones possessed the most superior User Interface, compared to Ericsson or Motorola).

Jobs now wishes to make the case for where the current crop of alleged smartphones lies in his graph:

And he actually refers to them, something some of those in advertising would say is to break the Golden Rule of naming your competitors. But so confident is Jobs that Apple’s iPhone is a “leapfrog” above these (he actually uses that term, below) that he is not concerned to both name them, and later show them.

And he actually refers to them, something some of those in advertising would say is to break the Golden Rule of naming your competitors. But so confident is Jobs that Apple’s iPhone is a “leapfrog” above these (he actually uses that term, below) that he is not concerned to both name them, and later show them.

Having heaped scorn on the existing batch of dumb, feature and so-called smartphones, Jobs shows us why the iPhone has a reason for being:

Jobs says Apple wants to make a product that is “way smarter… and easier to use” than the usual suspects, and – before we’ve even seen what it looks like – places the green iPhone icon in the top right quadrant, well away from the others, visually in a category all on its own. If the tech industry had really studied this diagram during the keynote, rather than chuckling at Jobs’ seeming dumbing down of his Business School 101 graph – a true Jobsian misdirection – they may have detected the tsunami of innovation and change that was about to be unleashed upon them. Through hubris, inertia and groupthink, Nokia, Sony Ericsson, Motorola, Google, and especially Microsoft were caught flat-footed, and it started with such a simple, yet revealing graph.

Jobs says Apple wants to make a product that is “way smarter… and easier to use” than the usual suspects, and – before we’ve even seen what it looks like – places the green iPhone icon in the top right quadrant, well away from the others, visually in a category all on its own. If the tech industry had really studied this diagram during the keynote, rather than chuckling at Jobs’ seeming dumbing down of his Business School 101 graph – a true Jobsian misdirection – they may have detected the tsunami of innovation and change that was about to be unleashed upon them. Through hubris, inertia and groupthink, Nokia, Sony Ericsson, Motorola, Google, and especially Microsoft were caught flat-footed, and it started with such a simple, yet revealing graph.

Of course, Jobs was a master story creator and teller, and not all scientists are so gifted or empowered.

But let’s see some of the easy catches scientists can make to at least give themselves a better chance of successfully engaging and persuading their audiences.

To do this, I need to remind you of my previous blog entry, where I asserted your presentation needs to stand alone, be its own entity, and not merely a cut and paste job from your paper publication.

Here’s why:

What you’re seeing here is a Powerpoint slide, not a screenshot of a journal PDF from Neurobiology. It was used in a medical presentation I located in a random search using Google.

What you’re seeing here is a Powerpoint slide, not a screenshot of a journal PDF from Neurobiology. It was used in a medical presentation I located in a random search using Google.

Now there is a place for showing you have gone to the original source for your slide. I do this on a frequent basis, although I always start with the first page of the article, and sometimes even show the cover of the journal opening using Keynote’s Flop (right to left) transition to suggest a page turn of the cover.

I then use Magic Move to focus in on a selection of the page, as in the diagram above. In the Powerpoint from which this slide is taken, there is simply a change of slide.

There are some issues though with this slide, however. For one, the images are heavily pixelated. Not such a serious problem however, and those at the back of the room probably won’t notice it. But what is disconcerting no matter where you sit is the tiny print explaining the meaning of the figure. This is fine to include in a printed journal document, but in a slide in a live presentation it’s out and out junk. Clutter. Distraction. Attention splitting. Confusing, Frustrating. Message denuding. This is ironic considering the figures are comparing brain activation areas in dyslexics and normals on certain reading tasks.

How would I do this instead if it was me showing this figure? Clearly, the figure is intended for meaning extraction by profoundly knowledgeable audiences. The use of acronyms and letters is meaningful to only such audiences and would require significant explanation for a lay audience.

What the author is trying to do is show differences between two groups on specific tasks. But in showing us all the twelve images (6 pairs) simultaneously we would have to have significant prior knowledge to know the meaning of these image variations.

For a lay audience, the idea would better be handled by taking some time to show normal responses on the tasks, then contrasting them step by step (once more using Magic Move to move from pair to pair of images) showing the changes for dyslexics across tasks. In other words, tell a story about the tasks and what they are testing for, and how it is that the images portray significant differences between the test groups.

Here’s another example from a colleague with a purpose built slide, not one taken directly from a publication:

What we’re seeing are two different measures of the same subject group side by side. The presenter first talks about one measure, say the one on the left, then transfers his, and presumably our, attention to the one on the right.

But why have both appear simultaneously and split our attention when the presenter can only describe one at at time? Where would the harm be in just using one graph per slide?

Here’s another slide from the same presentation to drive the point home:

Now, just because your software allows you to show four graphs at at time doesn’t mean you have to do it this way. It’s not like you’re giving handouts and trying to conserve paper. Unless indeed that’s what you’ve done, and have now asked your audience to turn to page 16 of their handout where you will walk them through each graph step by step. In that case, I don’t have an issue with this slide. Indeed, when I speak with academics they explain to me their students demand the slides ahead of class. And workshop attendees demand handouts to take something away with them for their cost of attendance.

(Aside: I never give handouts, before, during or after my workshops. I suggest at the beginning of the class how attendees can best make use of the visuals and information I’ll be presenting, and I let them know I will follow up with an email of links to services and ideas I will make mention of, including unplanned references spontaneously arising through group discussion.)

But unless you are making direct comparisons between the graphs and you need them all on the one slide, it’s just overwhelming for a live audience. What the presenter could do is:

1. Start with all four and say, “We conducted a series of four experimental procedures the results of which are summarised on this slide. Let start with the graph top left and have a closer look at what the results mean.”

2. From there, you use the Magic Move transition to zoom to that graph and explain to your audience what’s happening.

3. You do the same shift of attention for each of the remaining three graphs.

4. You zoom out again to show all four graphs and then offer a summary of what can be gleaned having exposed subjects to four experimental conditions, and where the data either advances a hypothesis, rejects it, or constructs a new set of hypotheses not previously considered.

Here’s a quick and dirty screenshow using Keynote 6 (KN6 falls over currently when exporting to Quicktime movies unlike the mature Keynote 5):

Here’s another slide from a Powerpoint show which demonstrates one of my other pet peeves:

Once more, we have two graphs on the one slide. What I really dislike is the now ingrained habit of labelling the Y (vertical axis) with English (not Chinese, or Japanese) words starting from bottom to top. It’s hard to read. Now if the idea is to say, “Yes but it signifies increasing levels (e.g. 80 – 200)” why aren’t the numerals also rotated 90 degrees counter-clockwise, like the words?

The other “explanation” I hear is that in space-constricted slides where screen real estate is at a premium, it’s easier to write words in a vertical plane to conserve space. Really? Look how much white space there is on this slide.

Surely, the designer could have taken one graph at a time, significantly enlarged it, and then found space to write the Y axis description horizontally, making it much easier to read.

What I do like about the slide is the author’s header, which specifically tells his or her audience the graphs’ meaning. It cues us in to look for the important elements in the slide, which the presenter then explains to us.

I almost always either use graphs with such an explanation header, or I completely leave off any descriptions, preferring to gently build the graph item by item, Jobs-style, drawing out important differences or similarities in a cohesive narrative.

A few more guidelines:

- If you are going to use visual elements like photographs, try and use one per slide rather than cover your slide with numerous smaller pictures overlapping each other. There needs to be a specific reason why a slide has multiple pictures, collage-style, which otherwise simply clutters the slides and divides audience attention.

- Make sure when using visuals they do not pixellate when you enlarge them. I have rejected truly brilliant photos in favour of less suitable photos (or none at all), if when enlarged, they pixellate. It’s just too distracting.

- Make sure you remove any watermarks on photos which are not your own. It’s just plain unprofessional.(UPDATE: Following a comment below, I want to be quite specific about this point.What I should have written is, don’t just drag and drop a watermarked image into your slide. Do the right thing and purchase the image, thus killing two birds with one stone.I believe Getty images have released a huge tranche of its materials for free use in personal blogs. Worth pursuing as is paid services like iStockphoto (which now sells movies and backgrounds), and similar. And there is also Flickr and Creative Commons images to pursue with correct attribution. Also see Matt Shipman’s recent Scilogs science communication blog article here for ideas and free resources.I use a paid app from Glencode called Viewfinder to help track down images this way. These third party helpers and more will be demoed at my Macworld workshop March 26 this year.)

- Be wary of mixing styles of data visualisation in the one slide. Look below at the slide for an example:

The task with the slide above is to give consideration to how an audience will respond to this very rich slide. Where should their attention go? To the pictures or the graph? Would it not be better to show one, then the other and use your speaking to make the connection?

There is now on the web an enormous library of guides for how to portray data sets visually. With the current emphasis on “Big Data”, there are now specialists in this area who can assist to produce complex charting which are useful for paper, convention expo or website viewing, but which overwhelm a slide unless you can use Magic Move to move around the slide bringing singular attention to each component. Here’s a Big data style expo stand I located today at an IT convention in Melbourne:

Also, go to the Roambi website here which makes apps for iPad and iPhones to assist with data visualisation on a large scale. Use it for inspiration.

Concluding remarks:

The challenge for scientists is that in the main they are using “small data” from their experiments, or “medium data” from meta-analytic studies then constructing the graphs themselves. This can be either using the built-in tools Powerpoint and Keynote offer, or purpose-built apps which can construct complex charts (eg. Excel and Numbers) then import them into your slidestack.

But whatever you do, make sure you stand back from your slide metaphorically and empathise with your audience. Ask if the slide is achieving your aim of providing persuasive information which best illustrates your ideas and findings, or is it there because science presentation dogma demands it.

In my next entry in this science-oriented series, I’ll look at the biggest challenge for scientists as well as those in the humanities: the use of text on slides. Is there a way to use text that still keeps audiences engaged and with the presenter, rather than reading and racing ahead?